Currently, there is a piece on “the average college student” (in the U.S.) making the rounds. It’s sparking both frustrated nodding about the problems in student performance and some eye-rolling about professorial arrogance.* Although I have met a number of students from the U.S., I have taught mostly in the Netherlands and in Germany, so my more positive experience might be owing to regional differences. But I’m not entirely sure. What’s perhaps most striking about the piece is that its merciless judgements are based on, well, not much exactly. In what follows, I’ll focus on Steven Hales’ remarks on reading, point out some problems, and then make some suggestions.

Hales’ section on reading starts by pointing out that “most of our students are functionally illiterate.” This is a drastic remark. Did he do tests? We are not told, but we get something like a definition detailing that this status amounts to being “unable to read and comprehend adult novels”. How the heck does Hales know? If he has any ways of learning about his students’ reading habits, he keeps them to himself. I’m left wondering how I would figure out what my students read. Well, of course I could ask them and sometimes indeed do. Could I judge from such conversations whether they “comprehend” the texts in question. That depends: partly on my own comprehension skills and partly on what students like to disclose. I remember my first shock when coming as a postdoc to Cambridge and being told by students as well as some colleagues that they had given up reading novels because there was only so much time – and that had to be spent on professional reading. What I’m saying is that there might be reasons for changing one’s reading habits, especially in academia, and it might be quite hard to figure out what a student actually thinks about their reading for pleasure, especially in a conversation with a professor. It’s not that I don’t believe Hales that at least some students don’t do the reading; it’s that Hales’ doesn’t tell us how he knows.

I’m not saying there are no ways of knowing or at least making educated guesses at what people read and comprehend. We do that all the time. So I’m not saying you need rigorous testing or anything like it to get an idea of whether someone read something and whether their reading aligns with yours. But given the drastic type of judgment, I’d expect a modicum of information about such ways. What this lack of information leaves me with is the assumption that the conversations informing Hales’ inferences about adult novels might have been quite superficial. Talking to my 8-year-old daughter about how she feels, I often get the reply “good”. If I don’t inquire further and about particular details, I’ll be left with that. More to the point, I know from my own student life that when a professor asked me something about my private endeavours or my thoughts on a text, I could become so shy that I would respond with utter nonsense. What now? Well, perhaps Hales did have thorough attempts at conversations about Richard Powers’ novels and he just doesn’t tell us. Perhaps some of these conversations didn’t go very well. The question to ask is: why! I’m not saying that Hales’ judgment is necessarily flawed, but I would expect it to be based on something – and the mere assertion that the average student is functionally illiterate suggests that something else is lacking here.

Since I like to inquire about reading habits among students and colleagues, I know that people can be become somewhat monosyllabic when you ask them about how they read. “I just, well, read,” is the reply I get most of the time. It takes time to tease out actual expectations from a genre or assumptions about the texts at hand. So what do you do when you think your students are bad at reading?

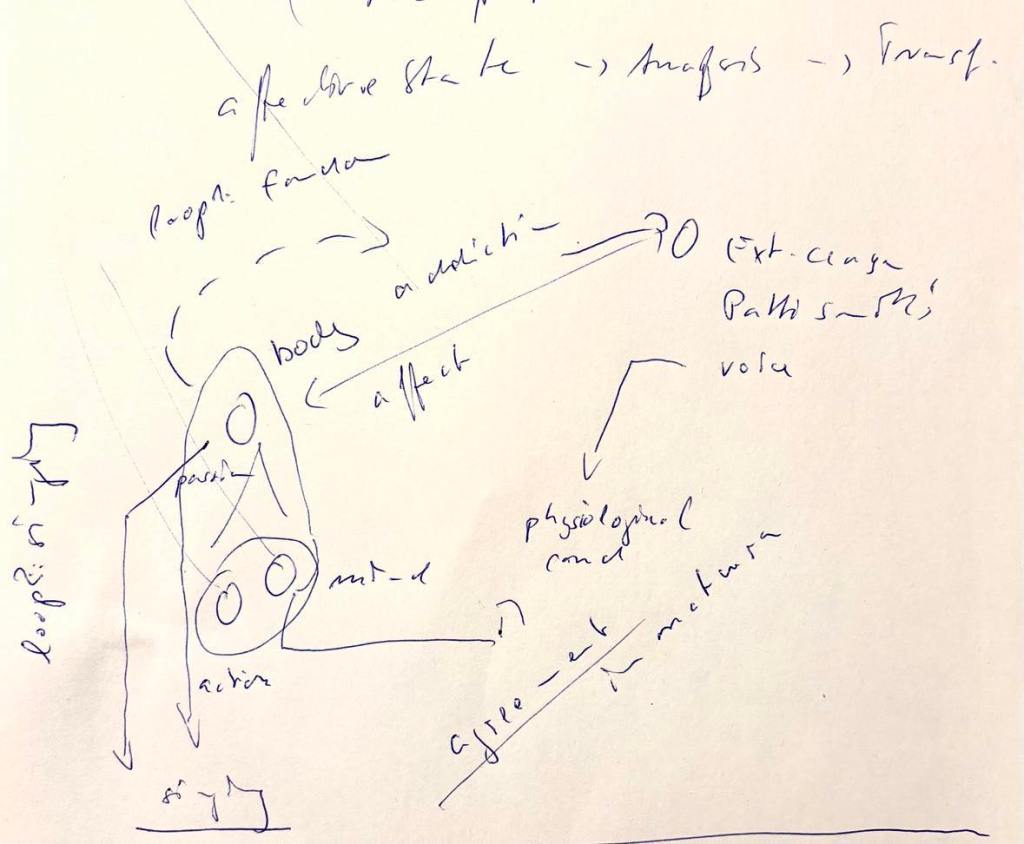

- First of all, ask them about it. Better still, start a conversation. To steer such conversations, it’s helpful to bear in mind that acts of reading are first and foremost defined through the interaction between readers. Reading is as much about belonging (to a certain group) and relating to styles and attitudes as it is about texts. So when it comes to conversations, the ‘text itself’ is a long way off. It’s the interaction between readers that settles important prior questions: Whether you belong to the same group, share expectations or desires or frustrations etc. Above all, it takes trust to converse about literature.

- A second point to bear in mind is that there is often a stark difference between reading, talking about reading, and performing relatedly in class. I might read all night through but never establish a comfortable way of talking about that in a semi-professional environment. Talking in front of peers or judgmental professors is quite different from enjoying reading. So, encourage such conversations very gently.

- Finally, what we Gen X people recognise as a reading culture does not immediately translate into the contemporary environment rich with gamification of interaction. Hales is ready to identify phones as the culprit, but that strikes me as too quick. Even if it feels very alien, we have to make an effort to find the reading culture outside of the places in which we expect it. Even social media foster reading, e.g. in the form of “BookTok”.

So on the whole, many of the problems described might be owing to expectations being at odds. Of course, some people really don’t like to read. But if you call them “illiterate” it strikes me as setting a problematic example if all you offer is your very own word for it.

______

* See also the blogs Daily Nous and Leiter Reports for extensive discussion.