Where do I begin? I’m getting into a new genre, fairly new at least for me: autosociobigraphy. While the term seems to have been coined by Annie Ernaux (see here for a volume on the genre), this kind of autobiography is perhaps not entirely new: As I understand it, it is an autobiography that does not merely give an account of one’s own life, but also presents it as a sociological or political analysis.* So this genre doesn’t just add a bit of reflection. Rather, it seems to be designed as an approach to (social) reality through a first-person narrative. Of course, sociology is not the only discipline in which this kind of approach is a clear enrichment. But although we also see autobiographies of philosophers and receive them as philosophical works, the potential of this genre leaves much space to be explored.** So, how about an autophilobiography? After all, a decidedly personal approach opens up the possibility to give pride of place to experience – a concept much cherished but also often banned for a supposed lack of universality. A fairly recent attempt at an autobiographical approach to philosophy I can recommend is Michael Hampe’s What for? A philosophy of purposelessness (Wozu? Eine Philosophie der Zwecklosigkeit). Reading this made me think that this is what I, among other things, want: If you are a more regular reader, you’ll know that I attempt to use a decidedly personal perspective now and then to make a point (a perhaps obvious piece is the one on the phenomenology of writing). Yet, once we allow that the autobiographical approach doesn’t have to be implemented in an entire book, we can see that there are a lot of reflections that are worthwhile bits of philosophy in this sense. Let me give just one example:

Being interested in the history of music in the 20th century in particular, I swallowed Tracey Thorn’s Bedsit Disco Queen where she describes the music scene of her early years before Everything But The Girl was formed in Hull, England. This as well as her more recent Another Planet can certainly count as autosociobiographies. While Thorn is a great singer and writer, I was equally taken by her reflections on singing in her essay collection Naked at the Albert Hall. Reading her account of singing inspired me to reconsider Spinoza’s philosophy of mind and particularly his account of philosophical therapy (I just finished a paper draft involving Thorn and Spinoza). I think that Thorn, while describing her way into singing, is really expressing a kind of reflection that Spinoza would deem an approach to philosophical therapy in the sense of re-ordering ideas about what matters. Let me just quote from her first essay in Naked at the Albert Hall:

“When did you know you could sing? people ask me. How did you even start? Where does your voice come from, is it from inside your head or inside your body? … I’ve written before that it was a disappointment to me when I realised I wouldn’t be Patti Smith, but that was a little way off in the future when I first heard her in 1979. … My first reaction to Patti Smith was one of possibility. I wanted to be her because a) on the cover of the record she looked like a boy, and I felt that I pretty much looked like a boy, and she made looking like a boy a beautiful thing; and b) the first time I tried to sing along with those opening lines on Horses, I realised in fact that I could sound like her. … Low, dark boyish, it existed in a space that seemed familiar, and contained the echoes of the sound I was tentatively exploring in the privacy of my bedroom. Joining in with her I found that we did indeed occupy the same ground, and without knowing how or why I had an immediate sense of my voice ‘fitting’. Imagining this to be a conceptual ‘fit’, I of course believed that I sounded a bit like Patti Smith because we were alike, it was a metaphysical connection being made. And in doing so I fell into the first and most basic misconception about vocal influence – the idea that it transcends the physical. Now I believe that the reason she implanted herself into my imagination as my first vocal influence was the simple accident of vocal range … My perfect, ideal range. Still the place I most like to sing. … Almost the entire Horses album is pitched perfectly for me … Joining in with Patti on these songs was a joyous experience, utterly secret … The basic physical coincidence of our vocal ranges connected us not just ideologically, but physiologically. … The lungs propel air, which passes through the vocal chords, making them vibrate and producing the sound we use for either speaking or singing. But unlike any other instrument, these components are your own actual body parts, and the sound you make is both defined and limited by your anatomy. As an instrumentalist you might practice and adapt your technique in order to follow the style and sound of players you like … But as a singer there is only so much you can ever do to adapt the sound of your voice to emulate singers. We label as inspirational those whose sound lives somewhere close to our own …” (Thorn 2015, 3-6)

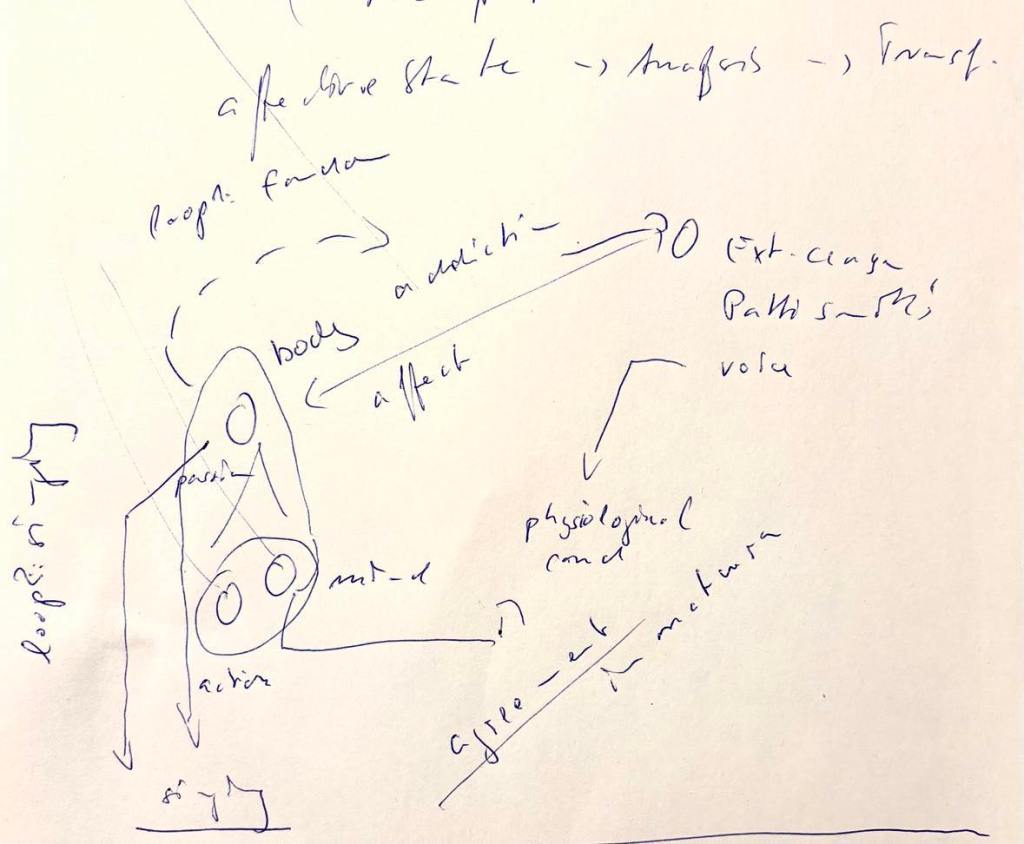

There is a lot in these observations. A couple of years ago, I took her observations as an anchor to think about active forms of listening to music. But now I think this goes deeper and exemplifies how we re-evaluate experiences and thus change (narratives about) ourselves. Apart from the aspiration and attraction depicted, it is clear that the author, Thorn, takes her body to be in agreement with that of Patti Smith, at least as far as the conditions for singing are concerned, and that that agreement is physiological. At the same time, the author realises that this agreement is easily confused with one of personality. But what she is describing is a common concept of her physiologically determined vocal range in agreement with that of Patti Smith. In Spinoza’s terms, Thorn, getting this more distinct concept of her physiological likenesses with Patti Smith, is revealing an agreement in nature. Arguably, while the initial exposure to Smith’s voice in 1979 is a confused attraction, the account Thorn gives in 2015 is a therapeutic disentanglement of the initially confused concept, distinguishing the external or distal cause, Smith’s voice, from the internal or proximate cause, her own voice, and the resonance between them, i.e. the agreement.

(An early attempt at scribbling down Tracey Thorn’s account as it relates to Spinoza’s Ethics)

____

* Dirk Koppelberg kindly corrected me on FB and offered the following charactrisation: “As I read Annie Ernaux, she does not “also” present a sociological or political analysis of her life but delivers an aesthetically arranged and composed description of it that illuminates certain sociological and political determinants of her life. This kind of writing seems to me an aesthetically challenging alternative to a sociological and political analysis in the strict sense.”

** The autosociobiographical approach will also figure in a project on reading as a social practice that I’m currently planning together with Irmtraud Hnilica. Stay tuned for updates on this project soonish.

Looking forward to your reading project! Best, Dirk

LikeLiked by 1 person

“When did you know you could sing?” This question asks about a beginning as a contact between knowing about yourself and being able to do something. For me, it gives me an idea that parallels (partial) Jacob Kounins (an educational scientist) withitness with this relationship of selfawareness and being able to do something. The term withitness describes that a teacher demonstrates pupils that she knows what they are doing in the classroom.

“My first reaction to Patti Smith was one of possibility” Patti Smith shows that it is possible to sing like Patti Smith, under a sample of circumstances…

Withitness, that means for me to handle circumstances, physical or otherwise. And to perform this handling. It must be public to getting resonance.

“After all, a decidedly personal approach opens up the possibility to give pride of place to experience”

Withitness names a personal approach to deal with human acts in a public sphere.

“But now I think this goes deeper and exemplifies how we re-evaluate experiences and thus change (narratives about) ourselves.”

Here stopps every possible parallel between the concept of autobiographical thinking with relations to social, political or philosophical analysis and the educational conept of withitness.

Thank your for this little impetus for thinking.

LikeLiked by 2 people