“What the philosopher establishes in their labors are not truths or theses, but rather scores, scores for thinking with.”

Alva Noë, The Entanglement, 115

If it’s true that so many people and especially ‘students these days’ fail at reading, there must be an ethics of reading. And of course, there is more than one. While many ideas in this field are revolving around the relation between reader and text (just think of the principle of charity), I’m currently more interested in the relation between readers. After all, it’s not so much between reader and text but between readers within a certain group that we try to enforce certain values.* Spinoza or his œvre will not show much offence, if you read sloppily. But your instructor, your fellow student or your colleague are already waiting for their gotcha moment. Indeed, many philosophy classes are thinly veiled occasions for blaming others of sloppy reading or, if they’re aiming higher, of missing the argument. What many philosophers or indeed other academic readers tend to overlook is that such (ethical) standards are relative to the profession or shared philosophical endeavour. If you’re reading for pleasure or reciting some passage to a friend, quite different standards might apply.** But even within philosophy, there are different sets of standards. In what follows, I want to look at these standards more closely, hoping to suggest that many common complaints about students these days etc. might be off the mark.

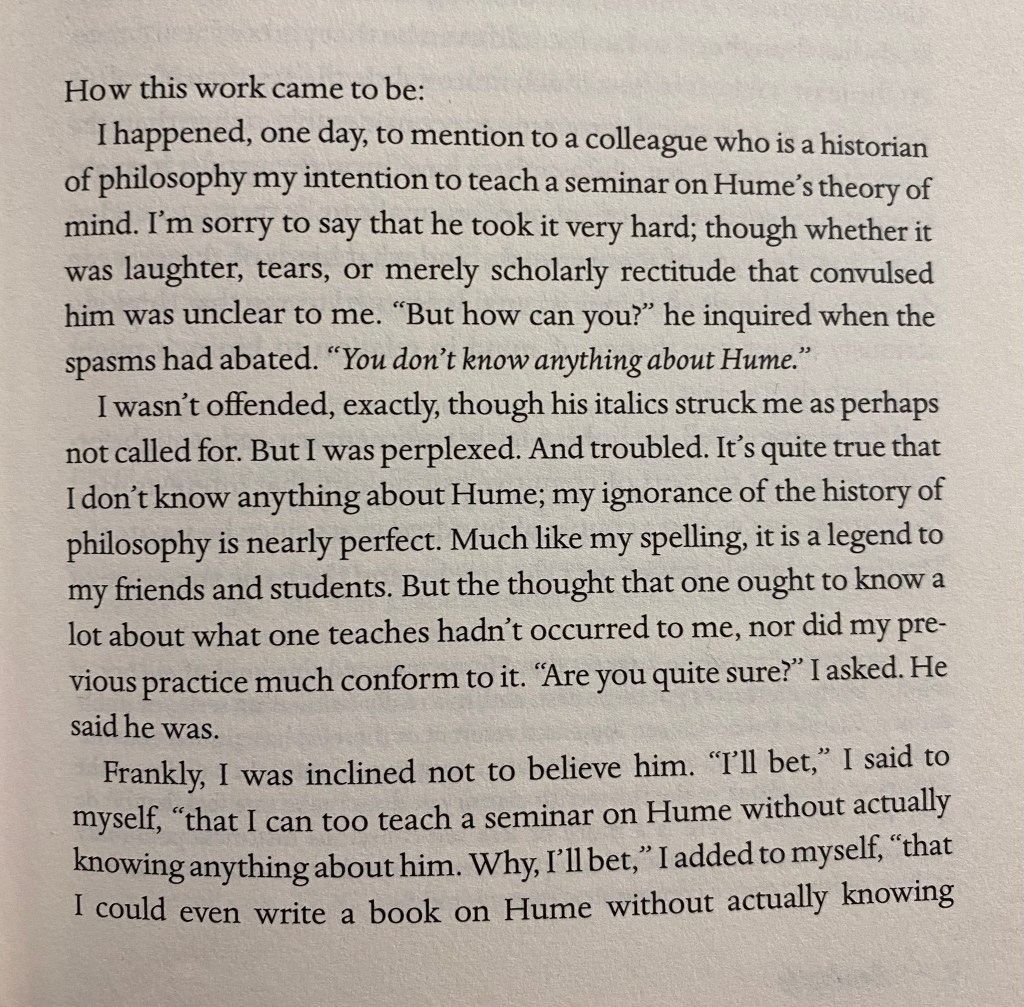

The ‘fake it till you make it’ reader. – I guess we all know this particular student who comes to class, is rather quiet when we ask for a summary of the text, but greatly enlivens the discussion when we turn to a particular argument. As instructors, we can sense that this student “didn’t do the reading”, but we let them get away with it – just this once – because it’s the discussion we care about most for the moment. If you haven’t been this student yourself, here is how it works: You just wait till the discussion reaches a very particular point (and it will), then you make up your mind about the point, deriving most insights from the summaries before and the heat of the moment. If you actually did bring the text, you might quickly search for the pertinent passage and even shine with terminological digressions. It’s a great skill, but it doesn’t require the kind of devoted reading that is encouraged by old dons. The skill is not based on “wrestling with the text” but on distilling crucial information and turns from what is being said. By and large, this kind of skill is greatly honoured in philosophy classes and in essay writing. We use words like “smart” to describe such behaviour, even if we might chide the student for not going all the way and reading the damn book properly. (By the way, I don’t think Jerry Fodor lied when he said that he thought he could write a book about Hume “without actually knowing anything about Hume.”)*** Hence, we might say that the ethical core value in place is not so much being a serious reader but rather being a serious discussant of pertinent ideas.

Now change just some parameters. – Instead of listening to your fellow students, you ask ChatGPT for a summary and for what’s in certain paragraphs. The same honoured skill is applied, but instead of honouring the skill we now focus on the decline of mankind as we knew it. But has anything relevant changed in what the student does? Remember, the student didn’t read the originally set text but gathers information from a likely somewhat flawed summary. Granted, the student might be better off listening to fellow students rather than feeding off tech products, but for the particular ethics applying to what happens in class or on the page, the student may still be doing what matters most, i.e. engaging in a serious discussion of a thesis or argument. In fact, many philosophers I know trust their rational reconstructions much more than poring over the ancient texts. We even have debates about whether we should really have students read an actual text by Kant, let alone the original German, rather than, say, the smart secondary texts in our ubiquitous “just the arguments” summaries. So if we don’t care all that much about teaching “the text”, let alone “the original”, why do we worry so much about students when they take this endeavour to the next level?

I’m not saying textual scholarship doesn’t matter; and you wouldn’t have much fun in my history of philosophy classes when ignoring the texts. What I’m saying is that different ethics of reading apply to different sub-disciplines in philosophy. I often tell students that, while philosophers care most about problems, historians of philosophy also care about texts. So the stakes are different. And it’s this difference that we signal to our students when we focus on, say, the structure of the argument as opposed to the frilly bits and bobs in the text.

______

* I’m greatly inspired by Adam Neely’s The Ethics of Fake Guitar, who makes a similar point about adherents of different genres of music favouring different core values.

** Already in relation to an earlier post, Marija Weste convinced me that there is less of a difference between different types of texts (say, philosophical texts versus novels), but much more of a difference between professional academic reading as opposed to non-professional kinds of reading.

*** Here is the passage I have in mind from Fodor’s Hume Variations:

However, ChatGPT tells me: “Jerry Fodor’s claim that he could write a book on Hume without knowing him is not meant to be taken literally. It highlights his approach to philosophy, which is to focus on the enduring theoretical insights of philosophers like Hume, rather than necessarily adhering to historical interpretations. Fodor uses Hume’s ideas as a source of inspiration for his own work in cognitive science, particularly his theories about the mind and language.”