Hier finden Sie das Video meiner Antrittsvorlesung Lesen als soziale Praxis:Über den Objektivismus im Lesen von Texten, gehalten am 10. Dezember 2025 an der FernUniversität in Hagen. Falls das Video gerade nicht abgespielt werden kann, finden Sie hier die Originalversion auf der Webseite der FernUni. Eine englische Übersetzung des Texts finden Sie hier. Der Vorlesungstext findet sich unter dem Video.

Lesen als soziale Praxis: Über den Objektivismus im Lesen von Texten

Lassen Sie mich mit einer Frage an meine Kolleg*innen aus der Philosophie beginnen: Wie können wir ein ganzes Forscherleben mit einem Kapitel aus Aristoteles‘ Schriften verbringen und zugleich glauben, wir können die Lektüre einer studentischen Hausarbeit in rund zwei Stunden erledigen? Schließlich können doch beide Texte gleichermaßen enigmatisch sein. –

Ich habe die Frage mehrfach aufgeworfen und sehr interessante Antworten erhalten. Worüber die Frage wie auch die zahlreichen Rechtfertigungen meines Erachtens deutlichen Aufschluss geben, ist unsere Lesekultur. Der Unterschied wird natürlich gern mit Blick auf die Professionalisierung des Lesens gerechtfertigt. Nichtsdestotrotz sind wir als Gelehrte und Lehrende Vorbilder in den Fachkulturen. Schauen wir also genauer hin! Zumindest mit Blick auf die Textsorte (hier Aristoteles, dort eine studentische Arbeit) sollte es keine gravierenden Unterschiede geben: beides sind im weiten Sinne wissenschaftliche Texte. Der wirklich gravierende Unterschied liegt vielmehr in einem sozialen Faktor begründet, den man hier im Rekurs auf Miranda Fricker als epistemische Ungerechtigkeit bezeichnen könnte. Es sind nicht irgendwelche Eigenschaften des Textes, sondern bestimmte Vorannahmen der Gemeinschaft der Lesenden, die zu dieser Ungerechtigkeit führen. Diese Vorannahmen sind nicht einfach Ihre oder meine privaten Meinungen über Aristoteles, sondern sie sind in einer langen Geschichte strukturell verankert bzw. institutionalisiert, und zwar in Form einer bestehenden Kanonik, die sogenannte Klassiker vor Studierenden rangieren lässt.

Nun werden Sie vielleicht sagen: Naja, das gibt es. Gleichwohl sind solche Vorannahmen dem Vorgang des Lesens doch selbst äußerlich, gewissermaßen Kontext, Beiwerk, aber doch nicht zentral für die Auseinandersetzung mit einem Text. Der Text muss aufgrund ihm immanenter Merkmale gewissermaßen dekodiert werden und steht damit gleichsam für sich. Objektiv.

Dieser geradezu klassische Einwand ist durchaus typisch, nicht zuletzt in der Philosophie, aber auch in anderen Disziplinen, weshalb ich mich in meinem Vortrag wesentlich mit dessen Entkräftung beschäftigen möchte.

Allerdings geht es mir hier nicht darum, lediglich eine kleine Fehde auszutragen. Vielmehr halte ich die Frage nach dem, was Lesen ist, für eine fundamentale Frage der Philosophie. Überraschenderweise wird diese Frage, mit wenigen Ausnahmen, so gut wie nie in der Philosophie behandelt. Dabei ist das Lesen, zumal das genaue Lesen und Rekonstruieren von schriftlichen Texten ein, wenn nicht das Kerngeschäft der Philosophie. Fragt man aber Kolleg*innen, wie sie lesen, hört man oft – und das ist kein Witz – „ich lese halt einfach“. Es scheint mir aber ein großes Versäumnis zu sein, wenn man die Bedingungen des eigenen Tuns, also die Reflexivität im Lesen, nicht eigens betrachtet. Deshalb möchte ich nun – gemeinsam mit meiner Kollegin Irmtraud Hnilica – ein interdisziplinäres Langzeitprojekt über das Lesen als soziale Praxis entwickeln. Die These, dass das Lesen eine soziale Praxis sei, meint dabei genau das, was der gerade genannte Einwand bestreitet: Dass soziale Faktoren des Lesens eben kein Beiwerk, sondern zentral für das Lesen und die Entwicklung durchaus unterschiedlicher Lesekulturen sind.

Im Folgenden möchte ich daher erstens einen Blick auf unsere Lesekultur werfen, die den genannten Einwand insofern befördert, als sie Texte für etwas objektiv Gegebenes hält. Hier interessiert mich die Frage, wie kommt es eigentlich und seit wann ist es so, dass wir Texte für etwas objektiv Gegebenes halten. Aus dieser Frage wird sich zweitens ergeben, dass die unterstellte Objektivität der Texte eine Illusion ist. Drittens möchte ich skizzieren, was Lesen meines Erachtens ist. Damit Sie sich innerlich warmlaufen können, sage ich Ihnen aber schon jetzt, dass wir das Lesen vielleicht am besten verstehen, wenn wir es in Analogie zum Singen von Liedern betrachten, nämlich als ein zyklisches und ritualisiertes Tun. Es sind die Eigenschaften dieses sozialen Tuns, die objektivierend sind. Viertens möchte ich andeuten, wie die fortbestehende Illusion zu einer degenerativen Mechanisierung des Lesens führt. Abschließend möchte ich dann fragen, wie uns dieser Zugang beim Verständnis unserer und anderer Lesekulturen auch in der Praxis helfen könnte.

I. Zur Fundierung des Objektivismus in der Philosophie

Beginnen wir noch einmal mit dem Einwand, der Texte selbst als objektiv Gegebenes behandelt. Nehmen wir den Einwand ernst, so müssten sich zwischen den Texten eines Studierenden und des Aristoteles markante Unterschiede aufweisen lassen, die die unterschiedliche Mühe begründen. Noch bevor wir jedoch in die Texte selbst blicken können, wird uns die Vergangenheit, unsere Vergangenheit einholen. Ob wir wollen oder nicht, wir stehen in einer Tradition, die bestimmte Texte als sakral behandelt. Aristoteles gehört als Autor in diese Tradition, er galt fast 1000 Jahre lang als philosophus, als der Philosoph schlechthin. Den Versuch, die Texte dieses Autors als konsistente Äußerungen eines Genies zu lesen, wird man selbst bei seinen ärgsten Gegnern finden. Der Sakralisierung oder, etwas zurückhaltender, Kanonisierung von Aristoteles‘ und anderen Werken, folgt spätestens seit der sogenannten Aufklärung eine deutlich verschiedene Lesekultur. Gegen die umfassende Kommentarliteratur der Antike und des Mittelalters findet sich wiederholt und zunehmend emphatisch die Verdrängung genauen Lesens durch die Kultivierung des sogenannten Selbstdenkens. So heißt es etwa bei Schopenhauer:

„Wann wir lesen, denkt ein Anderer für uns: wir wiederholen bloß seinen mentalen Proceß. Es ist damit, wie wenn beim Schreibenlernen der Schüler die vom Lehrer mit Bleistift geschriebenen Züge mit der Feder nachzieht. Demnach ist beim Lesen die Arbeit des Denkens uns zum größten Theile abgenommen. Daher die fühlbare Erleichterung, wenn wir von der Beschäftigung mit unsren eigenen Gedanken zum Lesen übergehn. Eben daher kommt es auch, daß wer sehr viel und fast den ganzen Tag liest, dazwischen aber sich in gedankenlosem Zeitvertreibe erholt, die Fähigkeit, selbst zu denken, allmälig verliert …“ (1851, § 291)

Interessanterweise ist Schopenhauers Pessimismus gegenüber dem Lesen von ähnlichen Sorgen motiviert, wie heutige Ermahnungen gegen social media, in denen sich zugleich die Behauptung vom Verfall unserer Lese- und Denkfähigkeit Bahn bricht. Wenn Schopenhauer Recht behielte, sollten wir das Lesen vielleicht lieber lassen, oder? Doch gerade mit der Unterstellung, der Text enthalte die Gedanken anderer, die wir im Lesen bloß nachvollziehen, wird der Objektivismus in Bezug auf Texte gefestigt. So gelten bestimmte Texte als schädlich. Bereits im ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert hatte man gerade in Deutschland gegen die „Lesesucht“ gewettert, wobei besonders Jugendliche und Frauen zu den „Risikogruppen“ zählten. Gleichzeitig entfaltete sich in den theologischen und historischen Disziplinen die historisch-kritische Methode.

Und in der Philosophie entwickelte sich neben einer methodisch fundierten Kanonisierung von Klassikern, namentlich durch Autoritäten wie Kuno Fischer, zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts eine dezidierte Renaissance der Bemühungen der frühneuzeitlichen Royal Society um die Etablierung einer Idealsprache für die Wissenschaften, die einen entsprechende Texte als objektive Bezugssysteme zur Weltbeschreibung verspricht.

Eine Eigenart, die wir bis heute mit dem frühen 20. Jahrhundert teilen, ist die Idee, dass man schriftliche Texte rational rekonstruieren könne, indem man Argumente von historischem und rhetorischem Beiwerk trenne. So gelangt man von der Textoberfläche gleich zur Tiefenstruktur, kann die logische Form notieren und die Kernsätze in Prämissen und Schlussfolgerungen umformulieren. Diese Idee suggeriert natürlich, dass das Argument im Text drinsteckt und dass man es dort – nach einführender Unterweisung – suchen kann. Dementsprechend kümmert sich auch ein Großteil der gegenwärtigen Philosophiedidaktik nicht um das Lesen selbst, sondern um die Analyse von Argumenten. Inzwischen hat die Welle des so verstandenen Critical Thinking auch außerhalb der Philosophie all jene erfasst, die irgendwelche Kompetenzen lehren wollen.

Wie man Argumente analysiert, sollte man natürlich lernen, aber man sollte wissen, was man da genau tut. Man bietet eine bestimmte Übersetzung durch Auslassung und Substitution an. Man behauptet dabei aber einerseits, dass das Argument im Text steckt, andererseits aber, dass das Argument ohne Übersetzung unsichtbar bleibt. Gerade Anfängern wird dabei oft suggeriert, dass es hier eine korrekte Rekonstruktion gibt.

Schauen wir uns das aber mal an. Nehmen wir zur Illustration mal den berühmten letzten Satz aus Wittgensteins Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muss man schweigen.

- Sie können den Satz erstens positivistisch deuten: als Einschränkung auf das sinnvoll Sagbare durch die Naturwissenschaften. (Dann deuten Sie das „Muss“ als deskriptiv.)

- Zweitens können Sie den Satz mystisch-ethisch deuten: als Priorisierung des Unsagbaren als eigentlich Wichtiges. (Dann deuten Sie das „Muss“ als normativ.)

- Drittens können Sie den Satz als selbstwidersprüchlich und in diesem Sinne als therapeutisch deuten: Denn in ihm wird genau von etwas gesprochen, worüber man eben nicht sprechen kann. (Das „wovon“ benennt etwas, das im Reflexivpronomen „darüber“ als unsagbar ausgewiesen wird.)

Diese Deutungen widerstreiten einander zwar, lassen sich aber nicht nur durch den zitierten Satz, sondern auch durch die Kontexte des Tractatus und der späteren Schriften validieren.

Wenn Sie einmal gesehen haben, wie viele widerstreitende Rekonstruktionen es selbst von weiteren klassischen Texten gibt, werden Sie stutzig sein, was die Objektivität von Texten angehet. Es ist klar, dass die Analyse von entsprechenden Argumenten hier wesentlich auf einer Verständigung zwischen logisch geschulten Leser*innen beruht, bei der der Original-Text selbst oft als hinderlich gilt. Statt sich aber nun darauf zu konzentrieren, wie sich die Lektüre durch diesen Aushandlungsprozess unter Lesenden gestaltet, tut man weiterhin so, als würde man an der Optimierung der Rekonstruktion eines Klassikers arbeiten. Was hier entsteht, könnte man ohne Weiteres als fan fiction bezeichnen.

Nimmt man das nun ernst und nicht lediglich als Polemik, ist klar, dass sich die Philosophie in bestimmten Schulen durchaus in Nachbarschaft zu ganz anderen Literaturgattungen befindet. Aber auch das Insistieren auf philologisch strenger Lektüre nimmt in der Regel den Text als Quelle der daraus gewonnenen Doktrinen und Denkformen, wie dies auch durch die generelle Unterscheidung von Primär- und Sekundär-Texten suggeriert wird. Insgesamt kann diese Annahme in Bezug auf das Lesen als Objektivismus bezeichnet werden.

Wie aber sollte man diesen Objektivismus unserer Lesekultur verstehen?

II. Der Text als Möglichkeit von Lesarten in Deutungsgemeinschaften

Unter Objektivismus verstehe ich die Annahme, dass das, was wir dem Text zu entnehmen meinen, im Text selbst zu finden sei. Das ist einerseits eine korrekte Annahme, denn all die Leser*innen werden Ihnen bestätigen, dass sie ihre Interpretationen aus den Texten gewinnen. Natürlich muss man hier hinzufügen, dass ein Text in der Tat als eine Verkettung von Propositionen gelesen werden kann, die dekodierbar sind und auf deren Präsenz sich die meistern Leser*innen werden einigen können.

Andererseits ist es aber eine irreführende Annahme, was man schon daran sieht, dass über Interpretationen endlose Streitigkeiten bestehen. Denken Sie nur an das Wittgenstein-Zitat. Wenn dies zutrifft, ist der Objektivismus einerseits korrekt, andererseits aber irreführend. Einerseits korrekt, andererseits irreführend? Widerspreche ich mir hier gerade selbst? – Ich bitte um Geduld. Um den Widerspruch aufzulösen, muss man sehen, dass ein Text nicht mit seiner Lektüre identisch ist. Der Text ist eine Möglichkeit zur Lektüre, eine Lektüre hingegen ist die Realisierung im Text liegender Möglichkeiten. Im Anschluss an James Gibson kann man von Affordanzen sprechen, die der Text bietet. Wie Sarah Trasmundi und Lukas Kosch gezeigt haben, bietet Ihnen ein Text verschiedene Handlungsmöglichkeiten bzw. Lesemöglichkeiten. Welche Möglichkeiten Sie in Ihrer Lektüre nun konkret ergreifen, das hängt von weiteren Faktoren ab. Diese Faktoren sind – so meine These – vorwiegend sozial. Konkret heißt dies: Ob Sie eine Text so oder so lesen, welche Bedeutung sie dem Text also entnehmen, hängt von Ihren Interaktionen mit anderen Leser*innen ab.

Das merken Sie freilich meist gar nicht, weil Sie – zumal in unserer Lesekultur – oft allein mit einem Text sind. Aber im Grunde waren Sie nie allein mit einem Text: Als Kind wurde Ihnen, hoffentlich, vorgelesen. Als Schüler*in wurden Sie dauernd von anderen korrigiert. Und jetzt. Jetzt, da Sie erwachsen sind, hören Sie Stimmen. Nicht im pathologischen Sinne. Die Interaktionen mit anderen Leser*innen sind einfach meist implizit, gewissermaßen zu Gewohnheiten, ja Traditionen geronnen. Eine Gruppe, die bestimmte Interpretationsgewohnheiten teilt, möchte ich Stanley Fish folgend Deutungsgemeinschaft nennen. Fish verortet die Bedeutungsaushandlung für Texte in entsprechenden „interpretive communities“. Sie haben gelernt, Speisekarten zu lesen, und Sie wissen, was Sie mit Ihnen tun können. Und Sie werden eine Speisekarte nicht mit einem Gedicht verwechseln, oder? Noch bevor sie den Aufsatz auf Ihrem Tisch überfliegen, wissen Sie, dass er ein Argument enthält, weil es ja ein philosophischer Text ist – und enthielte er kein Argument, so wäre es ja gar kein philosophischer Text. So will es die Tradition Ihrer Deutungsgemeinschaft.

Es liegt also gerade an der Tatsache, dass ein Text nicht mit seiner Lektüre identisch ist, wohl aber Möglichkeiten zu Lektüren bietet, dass wir gern dem Objektivismus verfallen. Die Gepflogenheiten bestimmter Deutungsgemeinschaften werden so als Eigenschaften des Textes selbst ausgewiesen. Der Objektivismus mit Blick auf die Texte selbst ist aus dieser Perspektive eine Illusion.

Nun werden Sie vielleicht sagen: „Ach, ist doch nicht so schlimm. Ob ich die Gepflogenheiten nun in der Gemeinschaft oder im Text selbst zu finden glaube, ist doch egal, die Hauptsache ist: ich finde sie!“ – Das mag freilich sein. Zum Problem wird es aber, wenn Sie nach etwas suchen, es aber an der falschen Stelle vermuten.

III. Lesen funktioniert wie Singen

Wie also funktioniert Lesen? Natürlich lässt sich viel dazu sagen. Aber wesentliche Punkte lassen sich verstehen, wenn man Lesen in Analogie zum Singen von Liedern betrachtet. Schauen wir zunächst nochmals auf den Objektivismus.

Schriftliche Texte haben zwei wichtige Eigenschaften, so scheint es, die wir auch objektiven Gegenständen zuschreiben: Konstanz bzw. Wiederholbarkeit und Teilbarkeit. Wenn ich ein Buch zuschlage, so scheint es, ist der Text konstant dort, zumindest kann ich ihn wiederholt lesen. Und wenn ich Ihnen das Buch ausleihe, so scheint es, können Sie denselben Text wie ich lesen. So scheinen diese Eigenschaften der Wiederholbarkeit und Teilbarkeit dem Text selbst eigen zu sein.

Bei genauerem Hinsehen verhält sich die Sache aber anders. Die genannten Vorzüge stellen sich nämlich auch bei einem denkbar ungegenständlichen Tun wie dem Singen ein.

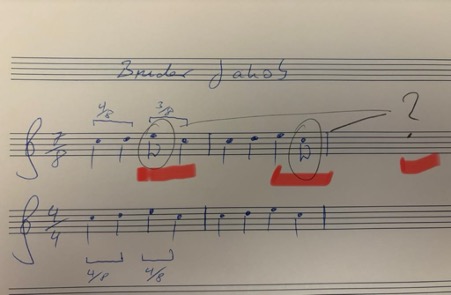

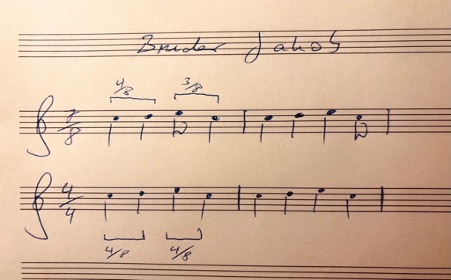

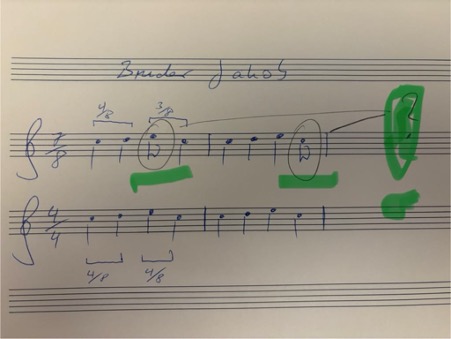

Hören Sie mal: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eV-7EJkmsd0&list=PLiAJPLHMA7zAKmiFzDc_gruaa6kpt_DhN&index=7

Sie hören gerade Bruder Jacob bzw. Frère Jacques! Die meisten von Ihnen werden es nicht nur kennen, sondern ohne Mühe auch dann singen können, wenn sie um 3 Uhr nachts aus dem Schlaf gerissen werden. Auch hier gilt, das Lied ist Ihnen konstant erinnerlich und Sie können das Singen wiederholen. Überdies können auch andere dasselbe Lied singen. Und Sie würden es sogar dann erkennen, wenn es jemand falsch intonierte.

Das Lied hat also eine gewisse Objektivität, es ist von unserer spontanen Performance und von unserer Vorstellung unabhängig. Aber es hat diese Objektivität nicht, weil es irgendwo schriftlich fixiert wäre. Wenn Sie genau hinhören, merken Sie, dass das Lied hier erstens im 7/8-Takt statt im üblichen 4/4-Takt gespielt wird und dass es zweitens viel reicher harmonisiert ist. Das relationale Objekt ist aber kein Text, da ist kein Gegenstand, auf den Sie zeigen könnten. Dennoch scheint es ein objektiv gegebener Bezugspunkt zu sein. Was die Objektivität bei aller Varianz stiftet, ist also nicht die Gegenständlichkeit, sondern es sind diese zwei Eigenschaften: Wiederholbarkeit und Geteiltsein mit anderen. Das Geteiltsein bzw. die Wiederholbarkeit durch andere spielt hier die tragende Rolle! Warum? Weil ich in meinen Wiederholungen ohne soziales Geteiltsein nicht korrigiert werden könnte. Allein könnte ich jeden Unsinn für eine Wiederholung halten.

Erst im Einklang mit anderen kann es so etwas wie eine richtige bzw. echte Wiederholung geben. (Dies ist die Konsequenz, die ich aus Wittgensteins Privatsprachenargument ziehe.) Erst wenn Sie affirmieren, dass es sich auch bei der 7/8-Version um „Bruder Jakob“ handelt, gilt es auch als „Bruder Jakob“.

Genau aus diesem Grund gilt beim Singen wie beim Lesen: Nicht die Gegenständlichkeit, sondern die geteilte Wiederholung, sprich die korrekte Wiederholung stiftet Objektivität. Was das Singen mit dem Lesen hier gemeinsam hat, ist, dass es in eine lange Geschichte sozialen Miteinanders eingebettet ist.

Wie das Lesen, erfuhren Sie das Singen vielleicht zunächst dadurch, dass Ihnen vorgesungen wurde, dass es wiederholt, verkörpert, gemeinsam und vielleicht sogar ritualisiert geschah. Ebenso wie Ihnen zunächst wiederholt in typischen Situationen vorgelesen wurde: das Lesen und Hören waren verkörpert, vielleicht in einem Bett mit einem Buch und Bildern. Gemeinsam, also vielleicht durch Ihre Mutter, Ihren Vater, vielleicht mit anderen Kindern. Und vielleicht als ein Ritual beim Zubettgehen, das Ihre Erwartungen geprägt und den Abend strukturiert hat. Es, das Singen wie das Lesen, ist Ihnen gewissermaßen als ein Ritual eingeschrieben. So lernen wir das. In diese biographischen Geschichten, nicht nur in eine abstrakte Tradition, ist das Lesen eingebettet.

Meines Erachtens sind es nun genau diese Faktoren, und besonders die Wiederholbarkeit und die Gemeinsamkeit, die dem Gelesenen Objektivität verleihen, zu der der Text ähnlich wie das Lied ‚an sich‘ aber allenfalls eine Möglichkeit bietet.

Was nun liefert uns diese Analogie mit dem Singen? Erstens verdeutlicht sie uns, wie wir mit Blick auf die Ojektivitätsfaktoren Wiederholbarkeit und Teilbarkeit Texten selbst eine Objektivität zuerkennen, die wir eigentlich aus der sozialen Einbettung gewinnen; anders als bei Texten, sind bei Liedern nämlich gar keine Objekte auszumachen. Zweitens verweist sie uns auf entscheidende soziale Orte und Situationen: Wenn wir uns also ernsthaft mit dem Lesen beschäftigen wollen, mit dem Aushandeln von Bedeutungen unter Lesenden, so müssen wir an die Orte gehen, wo dergleichen faktisch geschieht. Entsprechend wäre eine philosophische Beschäftigung mit einem Text des 18. Jahrhunderts darauf verwiesen, sich mit der Briefkultur sowie den Salons und überhaupt mit der Etablierung des Gesprächs als Ort des Denkens zu beschäftigen. Während es für viele von uns ganz selbstverständlich ist, dass wir Gespräche über Texte führen, ist diese Form, also das Gespräch, doch selbst irgendwann entstanden und hat – so eine meiner Folgerungen aus meiner Leitthese – die entscheidende Rolle für die Bedeutung bzw. den Gebrauch von Texten bestimmter Genres. Das Gespräch ist, neben dem Peer-review-Verfahren ein entscheidender Ort, in dem sich nicht zuletzt die philosophische Lesekultur ereignet. Entsprechend können Sie die unterschiedlichen Wittgenstein-Deutungen in ganz unterschiedlichen Diskussionen bzw. Communities verorten: die positivistische Deutung im Wiener-Kreis, die mystische bei Elisabeth Anscombe, die therapeutische etwa bei Peter Hacker.

Die Grundidee ist also: Die Texten zugeschriebene Objektivität ist eine Illusion, die durch (im Text liegende Affordanzen) aktualisierende Eigenschaften des Lesens suggeriert und in den Text zurückprojiziert wird. Lesen als soziale Praxis ist (wie singen) wiederholend, sozial divers verfügbar. Nicht der Text, sondern soziale Lektüre stiftet Objektivität.

So schreibt Suresh Canagarajah: „Meaning has to be co-constructed through collaborative strategies, treating grammars and texts as affordances rather than containers of meaning.

Das ist genau der Punkt, den ich auch zu machen versuche: Texte enthalten keine Bedeutungen, sondern bieten Affordanzen bzw. Möglichkeiten.

IV. Die Folgen der Illusion: Die Degeneration des Objektivismus zum mechanischen Lesen

Wenn das Gesagte zutrifft, so kann es auch sein, dass bestimmte Lesekulturen wieder verschwinden oder sich wandeln. Das bedeutet aber nicht zwingend, dass wir das Lesen verlernen, sondern vielleicht nur, dass sich die Art des Lesens und die Orte, an denen Bedeutungen ausgehandelt werden, ändern können. Das merkt man übrigens nicht nur mit Blick auf Technologien jüngeren Datums, sondern auch im täglichen Geschäft, insbesondere in der Lehre. Ich glaube aber, dass die noch stets verbreitete Illusion, Texte selbst seien objektiv, zu einer Degeneration in unserer Lesekultur führt. Und hier bin ich wieder bei meiner Eingangsbeobachtung, dass wir ein Leben mit einem Aristoteleskapitel, aber vielleicht nur zwei Stunden mit einer studentischen Arbeit verbringen.

Diese Praxis, die übrigens gerade auch mit einer zunehmenden Alphabetisierung, der sog. Massenuniversität und der gleichzeitig stagnierenden Zahl an Lehrenden zusammenhängt, könnte man sagen, wird zunächst als aus externen politischem Druck kommend erlebt – und doch richtet man sich zunehmend so in ihr ein, dass die Vorgaben für studentische Textproduktion – zumindest in den Niederlanden und Großbritannien – ihrerseits so schematisch sind, dass man tatsächlich nach 20 Minuten Lektüre urteilen zu können meint, ob die Anforderungen erfüllt sind. Eine solche Mechanisierung für das Schreiben und Lesen ist natürlich nur zu rechtfertigen, wenn man glaubt, dass Texte selbst objektive Entitäten sind, die dementsprechend entweder gut oder schlecht sind. Diese Mechanisierung ist übrigens keine Folge von ChatGPT. Vielmehr ist es umgekehrt so, dass eine sich dahin wandelnde Lesekultur konsequent einer solchen Technologie zu bedienen lernt.

Aus den Niederlanden weiß ich, dass die Mechanisierung des Lesens bereits in den Grundschulen greift, wo man von Beginn an begrijpend lezen unterrichtet, um Fragen nach der Textstruktur in Multiple-Choice-Tests abzuprüfen und sich denn zu wundern, dass die meisten jungen Leute keine Lust am Lesen haben.

Es scheint so, dass solche uninspirierten Vorbilder zu Leser*innen führt, die ihrerseits als Textproduzenten für Prüfungen Texte fabrizieren, die kaum gelesen werden. Warum also sollte man sie noch selbst schreiben? Warum selbst lesen?

All dies sind freilich Entwicklungen, die man zumindest an den Universitäten nicht unabhängig von der Einführung des New Public Management in den 1980er Jahren beschreiben kann. (Was nützt es, einem Studierenden zu sagen, man möge in den Text schauen, um ihn zu verstehen, wenn es um diesen Text herum kaum Interesse daran gibt. Nein, nicht etwa sind die Universitäten sind Elfenbeintürme; vielmehr haben sich kulturelle Wüsten um die Universitäten herum gebildet, in denen wir vor allem Stakeholder*innen statt Deutungsgemeinschaften sehen. Aber diese Kritik ist alt und auch ein bisschen einseitig.)

Denn natürlich gibt es sie, die Orte, an denen nach wie vor die Bedeutung von Texten ausgehandelt wird. Wir finden Sie auf Literatur- und gar Philosophiefestivals, in den sozialen Medien unter Booktok, in oft studentisch organisierten Lesegruppen und natürlich auch in unseren Lehr- und Forschungsveranstaltungen. Hier ist das Lesen manchmal so explizit sozial, dass es geradezu performt wird. Auch das ist natürlich nicht ganz neu. Wenn wir uns für die Grundlagen des Lesens interessieren, müssen wir an diese Orte gehen.

Besonders interessant für unsere Lesekultur ist, denke ich, dass Large Language Models nicht nur das Vertrauen in die Authentizität, sondern auch in die Objektivität von Texten erodieren lassen. Wir erleben hier eine gewaltige Desakralisierung des Textes. Denn anders als die hinter biblischen Texten vermutete göttliche Autorität, vermuten wir nun ständig einen täuschen Dämon. Dementsprechend glaube ich, dass das akademische Aufbegehren gegen diese Desakralisierung auch ein Aufbegehren gegen das Sterben der Illusion ist, dass Texten selbst Qualität inhärent sei.

Diese Desakralisierung zu benennen heißt nicht, die großen Versprechungen einschlägiger Produzenten von KI-Produkten zu schlucken. Aber wir können diese Technologie auch dazu nutzen, uns selbst zu sensibilisieren dafür, dass es nicht die Texte selbst sind, sondern unser Lesen, unser Gesang, unsere Rituale sind, die Bedeutungen stiften und zu etwas Geteiltem machen.

V. Ein paar Schlussfolgerungen

Was nun folgt aus diesen Einsichten für die Praxis? Wie können wir durch solche Erkenntnisse die Lesepraxis verbessern? Zunächst möchte ich daran erinnern, dass unser Forschungsprojekt erst am Anfang steht. Aber wenn die Bedeutung von Texten im Lesen wesentlich durch die Interaktionen zwischen Leser*innen erschlossen ist, dann hilft es, nicht in den Text selbst zu starren, sondern sich zunächst stets zu fragen: Was erwarte ich von diesem Text? Was unterstelle ich, das er mir sagen soll? Soll er mir ein Argument für etwas liefern? Was mache ich, wenn der Text die Erwartung nicht erfüllt? Soll ich demütig denken, dass ich zu dumm dafür bin? Dass ich nicht zu dem Club der Leser*innen gehöre, die von sich sagen, dass sie solche Texte verstehen oder gar lieben? Und warum liegt dieser Schinken überhaupt auf meinem Schreibtisch oder in meinem Adobe Reader?

Wenn man sich durch diese Fragen genug verwirrt hat, kann man tatsächlich in den Text blicken und schauen, was da geschrieben steht, ohne gleich das Argument zu suchen. Die Leute sagen ja immer, man solle nicht nur lesen, sondern gründlich lesen: Was heißt das aber, gründlich? Soll ich besonders viele Farben wählen, um die unverständlichen Passagen zu markieren? Im Ernst: Diese Anweisung ist ähnlich hilfreich wie zu sagen, man solle sich konzentrieren. Wie mache ich das? In die Luft gucken und die Augen klug verdrehen? – Woran merkt man denn, dass man sich hinreichend gut konzentriert hat? Wenn man sagen kann, was die Gesprächspartnerin freundlich abnickt? Mit einer Speisekarte kann ich bestellen, mit einem Gedicht kann ich gut klingen, aber was mache ich mit einem philosophischen Text? Wann habe ich da was verstanden? Noch immer können wir das nur im Gespräch sehen. – Reicht das?

Nun, eine grundsätzliche Einsicht, die aus der meiner lesetheoretischen Betrachtung folgt, ist, dass ein philosophischer Text Möglichkeiten bzw. Affordanzen und mithin stets verschiedene Möglichkeiten zur Lektüre bietet. Es ist ein insbesondere in der analytischen Philosophie verbreiteter Mythos der Vollständigkeit, dass sich alle impliziten Möglichkeiten schlicht explizit machen lassen. Eine solche Vollständigkeit widerspricht aber der notwendigen Offenheit bzw. Unterbestimmtheit in Texten. Denken Sie gerne wieder an die Wittgenstein-Sentenz. Eine weitere, sehr einprägsame Illustration dafür ist die Hasenente, die der Möglichkeit nach eben beides bleibt. Mein Projekt wäre nun,, nicht das eine wahre Argument zu rekonstruieren, sondern unterschiedliche und ggf. einander widerstreitende Möglichkeiten offenzulegen. Demnach muss man akzeptieren, dass der Text verschiedene Deutungen ermöglicht, die in den unterschiedlichen Deutungsgemeinschaften erst gewonnen werden.

Für gewöhnlich entwickeln Philosoph*innen an dieser Stelle eine typische Angst vor dem Relativismus. Doch wie bereits Stanley Fish festgehalten hat, geht es bei einer Betonung der Möglicheiten nicht um eine relativistische Position, sondern um Pluralität. Eine solche Plurailtät führt aber keineswegs in Beliebigkeit. Was nun aber sind dann die Grenzen für diesen Möglichkeitsraum? Zunächst gibt es natürlich propositionale Grenzen: Sie können nicht sagen, ein Text behauptet Nicht-P, wenn er explizit P behauptet. Es sei denn, Sie erblicken Anzeichen für Ironie. Schon hier wird die Sache mit den Grenzen wieder schwierig; und Sie werden sich eben so oder so entscheiden. Darüber hinaus gibt es situationsbezogene Angemessenheitsbedingungen. Wenn jemand nach dem Weg zum Bahnhof fragt, ist es nicht angemessen, frei nach Robert Frost mit dem Sinnieren über weniger ausgetretene Pfade zu antworten. Ebenso wie man auf einer Antrittsvorlesung nicht Bruder Jacob anstimmen sollte. Oder doch? Natürlich können wir mit Konventionen brechen. So ist es zum Beispiel offen, ob Sie das Lied im Vierviertel- oder im Sieben-Achtel-Takt singen oder aber mit Sus-Akkorden psychedelisch reharmonisieren. Die Konvention gibt Ihnen etwas, mit dem Sie spielen bzw. singen können.

Dementsprechend trifft Alva Noë einen zentralen Punkt, wenn er philosophische Texte mit Partituren für das Denken vergleicht, die man auch sehr unterschiedlich interpretieren kann:

„What the philosopher establishes in their labors are not truths or theses, but rather scores, scores for thinking with. … The philosophy lives for us like a musical score that we – students and colleagues, a community – can either play or refuse to play, or wish that we could figure out how to play, or, alternatively, wish that we could find a way to stop playing.”

Ich würde nur ergänzen, dass in Analogie zur musikalischen Notation philosophische Texte eine Vielzahl von Interpretationen zum Leben erwecken kann. Hier haben wir nicht nur eine Hasenente, sondern einen ganzen Zoo mit möglichen Aspektwechseln.

Nun, das mag ja alles sehr schön klingen. Man darf aber nicht vergessen, dass Interpretationen nicht nach Belieben, sondern v.a. im Blick auf soziale Zugehörigkeit gewählt werden. Wenn Sie eine Interpretation wählen, gehören Sie vielleicht in einen Club, der gerade wenig in Mode ist. Das Problem mit meinen Auskünften ist also, dass sie auf ganz unterschiedliche Weise genommen werden können. Gerade Akademiker*innen fürchten Reputationskosten; deshalb gestehen sie ihr Unverständnis nur sehr ungern ein. „Diesen Text verstehe ich nicht“ heißt ja meist eher, „Der Autor ist zu dumm, es mir gut zu erklären.“ Wenn man hingegen ernsthaft und aufrichtig Unverständnis äußern kann, ist man wirklich einen Schritt weiter. Aber solche Demut muss man sich gewissermaßen leisten können. Deshalb reicht es nicht, das Gespräch zu suchen, man muss seine Scham überwinden. Man kann auch nicht gut singen lernen, wenn man sich allzu sehr vor falschen Tönen fürchtet.

Irgendwann aber kann man wirklich beginnen, die dunklen Stellen zu nennen und sich zu fragen, wo genau man aus welchem Grund nicht mehr weiterkommt. Reflektierte Konfusion ist dann ein genuiner Gesprächseinstieg. Denn wenn ein Text die Möglichkeit bietet, ihn zu verstehen, dann auch die, ihn nicht zu verstehen.