When I studied philosophy at Bochum (Germany) in the early nineties, there seemed to be a ban on images in philosophy. My teacher Kurt Flasch, for instance, was even reluctant use the blackboard.* To me, this seemed very strange at the time. I never asked him about it, but perhaps this “ban on images” goes back to one of his teachers, Max Horkheimer, who proposed the “Bilderverbot” as enabling a truly critical attitude to ideology. While a decidedly linguistic approach to philosophy is a crucial part of its history, I also think that it is owing to an underestimation of the senses and indeed experience as such. As I see it, the mere attempt to transform written thoughts into images or to combine these two media can afford a more holistic understanding of various issues. At the same time, our current practices are flooded by images and thus require a pertinent literacy. In what follows, I simply want to share my experience of teaching through images and close with a few thoughts non-linguistic media.

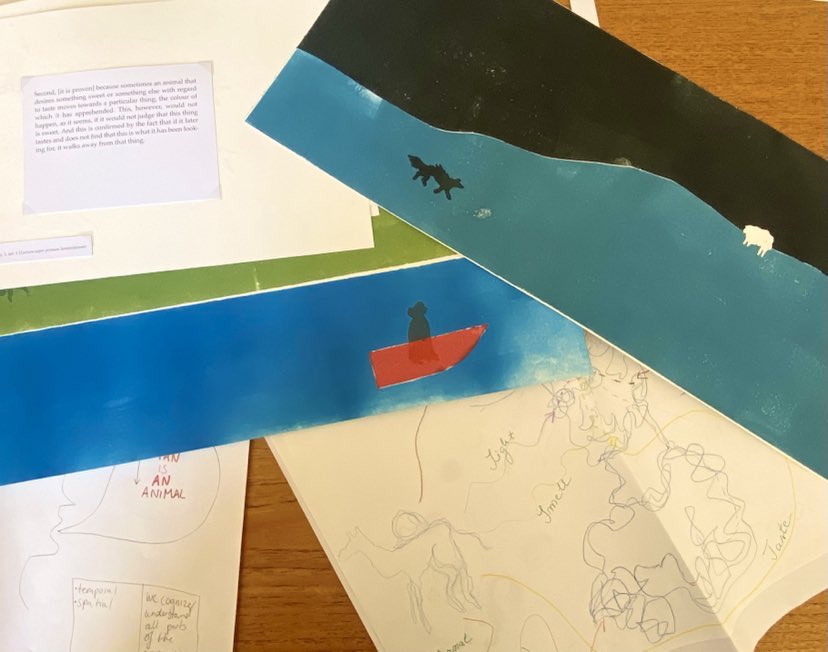

Introducing infographics. – Every now and then I have been trying to encourage students to make use of drawings, tables, graphs or other sorts of tools in their writing. We are obviously inclined to employ different styles of reasoning in keeping with our diverging talents or backgrounds. As Frege argued in his Begriffsschrift, we clearly see different aspects of thoughts when using different graphic representations of logical inferences. Following the encouraging advice of my Groningen colleague Benjamin Bewersdorf, I eventually took a random class in my course on Medieval Theories of Thinking by surpise: I wrote to my students a day before class asking them to bring coloured pencils, then handed out sheets of drawing paper and requested them to prepare infographics on the spot. I divided the students in three groups. One had to depict a conceptual distinction or problem, another had to depict a debate, and yet another had to depict a historical development. After chosing a topic, they had about thirty minutes to produce their work and then present (a) on the topic depicted and (b) on the experience afforded through the task. The outcomes were amazing.**

Three points struck me in particular:

- Having to do such work on the fly activates different people. – At least in my experience, there is often one particular group of students that runs much of the active discussions in the course. By contrast, this kind of task seems to highlight different talents and thus also different patterns of interaction, allowing otherwise quiet students to enter the stage and allowing new forms of collaboration.

- Using such media makes you reconsider what you (think you) know. – Having to illustrate a philosophical issue mercilessly brings out vague points or limits in our understanding. Not least presenting relations between items, concepts, interlocutors or even historical phases requires thinking through the way the relata are contrasted, for instance. At the same time, such presentations often afford an understanding of an issue in a flash of insight, rather than requiring you to move through sequential inferences.

- The previous two points yield a third one: a new experience. – Arguably, (philosophical) learning crucially depends on the kinds of experience we undergo when exposed to a problem. Experiencing the barriers and insights through transforming knowledge that is mainly linguistically available might allow connecting to your thoughts and those of others in a different way and anchor them more deeply.

Other media and other forms of philosophy. – Infographics make for an easy start. But I’d generally try and encourage students and colleagues to think about various media or art forms for inspiration. As my colleague Andrea Sangiacomo has shown, for instance, taking the term “meditation” seriously in Descartes’ Meditationes allows for an expanded understanding of what is at stake in this philosophy and indeed in much of the philosophical tradition (see here and here). Likewise, he is now delving into forms of dance – especially contact improvisation – to explore related ways of philosophical understanding.

Imagistic literacy? – It is one thing to recognise how the “embodiment” of thought can be explored by transforming linguistic thought to other sense modalities. Another point of such transformation is to recognise, for instance, how images work and how they connect to and are interwoven with linguistic communication. While social media are littered with images and videos, there is little understanding how they affect and indeed transform our lives from private interaction to warfare. I will keep my thoughts on this for another occasion. Suffice it to say that the attempt of transforming linguistic thought into images does not only yield new experiences; it also exposes the logical limitations of images.

_______

* Funnily enough, an introduction to philosophy based on infographics came out in 1991 (the DTV-Atlas Philosophie). But as you might imagine, it was much frowned upon and never used or carried openly back in the day.

** Depicted is some of the outcome from my 2022 course on What Is Thinking? Medieval Philosophy of Mind. I am very grateful to my students who did great work throughout the course. Special thanks to Sam Alma for pursuing an intriguing extended tutorial by combining an essay with infographics.

I have sometimes asked students to do this and some of them properly meltdown. But I never supplied colored pencils…

Still, I do think the meltdown is usually worth it. Thanks for the post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post! I think this should apply to history of philosophy as well as to philosophy. Embodied experimentation of historical philosophy practices is the way. Historians and archeologists have amazing results through experimentation and reenactement, historians of philosophy should look this way

LikeLike

Thanks for the post! I think this should apply to history of philosophy as well as to philosophy. Embodied experimentation is the way. Historians and archeologists get great results through these methodologies. History of philosophy should look this way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(sorry for multiposting)

LikeLike

Thank you! We touch on these things in our “Präsentationswerkstatt” at Bielefeld University, where we try to teach students how to present ideas with slides that are not just black text on white… This is often quite a challenge for all of us. But when the students really make use of the medium, the results are usually quite eye-opening.

LikeLike