Let me begin, once more, with a question for my colleagues in philosophy: How can we spend a lifetime on a chapter in Aristotle and think we’re done with a student essay in two hours? Both can be equally enigmatic.

I have raised this question several times and received some very interesting answers. What the question, as well as the numerous justifications, clearly reveal, in my opinion, is the state of our reading culture. The difference between the amounts of time spent on such texts is, of course, often justified with regard to the professionalization of reading. Nevertheless, we as scholars and teachers are role models in our respective disciplines. So let’s take a closer look! At least with regard to the type of text (a piece of Aristotle’s work and a student paper), there should be no significant differences: both are, in a broad sense, scholarly texts. The truly significant difference lies instead in a social factor, which, following Miranda Fricker, could be described as an epistemic injustice. It is not any particular characteristics of the text, but rather certain presuppositions held by the community of readers that lead to this injustice. These presuppositions are not simply your or my private opinions about Aristotle, but are structurally embedded or institutionalized in a long history, namely in the form of an existing canon that prioritizes so-called classics over students.

Now you might say: Well, that may well be so. However, such presuppositions are external to the act of reading itself, contextual, incidental, so to speak, but not central to engaging with a text. The text, due to its inherent characteristics, must be decoded, so to speak, and thus stands, as it were, on its own. Objectively.

This almost classic objection is quite typical, not least in philosophy, but also in other disciplines, which is why I intend to focus primarily on refuting it. However, my aim here is not merely to engage in a petty feud. Rather, I consider the question of what reading is to be a fundamental question of philosophy. Surprisingly, with few exceptions, this question is almost never addressed in philosophy. Yet reading, especially the careful reading and reconstruction of written texts, is certainly among the core businesses of philosophy. But if you ask colleagues how they read, you often hear—and this is no joke—”I just read.” It seems to me, however, a major oversight not to specifically consider the conditions of one’s own activity, that is, the reflexivity inherent in reading. In keeping with my long-term project with Irmtraud Hnilica, my thesis that reading is a social practice means precisely what the aforementioned objection denies: that social factors in reading are not merely incidental, but central to reading and the development of quite different reading cultures.

In the following, I would therefore like to first take a look at our reading culture, which promotes the aforementioned objection insofar as it considers texts to be something objectively given. Here, I am interested in the question of how and since when we have considered texts to be something objectively given. Secondly, this question will reveal that the assumed objectivity of texts is an illusion. Thirdly, I would like to outline what I consider reading to be. To help you prepare, I’ll tell you now that we might best understand reading by considering it in analogy to singing songs, namely as a cyclical and ritualized activity. It is the characteristics of this social activity that produce objectivity. Fourthly, I would like to suggest how the persistent illusion leads to a degenerative mechanization of reading. Finally, I would like to ask how this approach could help us in practice to understand our own and other reading cultures.

1 On the Foundation of Objectivism in Philosophy

Let’s begin again with the objection depicting texts themselves as objectively given. If we take this objection seriously, then there should be striking differences between the texts of a student and those of Aristotle, differences that justify the varying effort required. However, even before we can look into the texts themselves, the past, our very own past, will catch up with us. Whether we like it or not, we are standing in a tradition that treats certain texts as sacred. Aristotle, as an author, belongs to this tradition; for almost 1000 years he was considered philosophus, the philosopher par excellence. Even his fiercest opponents attempt to read his texts as the consistent pronouncements of a genius. The sacralization, or, to put it more cautiously, canonization, of Aristotle’s and other works has been followed, at least since the Enlightenment, by a distinctly different reading culture. Against the comprehensive commentary literature of antiquity and the Middle Ages, there is a recurring and increasingly emphatic push for the suppression of close reading by the cultivation of so-called independent thought. For example, Schopenhauer* writes:

“When we read, someone else is thinking for us: we merely repeat his mental process. It is like when the student learns to write with the pen going over the pencil marks of the master. So when one reads, most of the thought-activity has been removed from him. Hence the palpable relief we perceive when we stop to take care of our own thoughts and move on to reading. While we read, our head is truly an arena of unknown thoughts. But if we take away these thoughts, what’s left? So it happens that those who read a lot and for most of the day, in the meantime relaxing with a carefree pastime, little by little lose the ability to think – like one who always rides a horse and eventually forgets how to walk. This is the case of many scholars: they have read to the point of becoming fools.” (Schopenhauer 1851, § 291)

Interestingly, Schopenhauer’s pessimism regarding reading is motivated by concerns similar to today’s warnings against social media, which simultaneously assert the decline of our reading and thinking abilities. If Schopenhauer were right, perhaps we should give up reading altogether, shouldn’t we? But it is precisely the assumption that a text contains the thoughts of others, which we merely follow through reading, that solidifies objectivism in relation to texts. Not surprisingly, certain texts were considered harmful. As early as the late 18th century, there was much criticism of “Lesesucht” (reading mania), particularly in Germany, with young people and women being considered “at-risk groups” in particular. At the same time, the historical-critical method was established in theological and historical disciplines. And in philosophy, alongside a methodologically grounded canonization of classics, notably by authorities like Kuno Fischer, the beginning of the 20th century saw a distinct renaissance of the efforts of the early modern Royal Society to establish an ideal language for the sciences, promising corresponding texts as objective reference systems for describing the world.

One characteristic we still share with the early 20th century is the idea that written texts can be rationally reconstructed by separating arguments from historical and rhetorical embellishments. This allows one to move directly from the surface of the text to its deep structure, to note the logical form, and to reformulate the core statements into premises and conclusions. This idea naturally suggests that the argument is embedded in the text and that one can search for it there—after some introductory instruction. Accordingly, much of current philosophy didactics is concerned not with reading itself, but with the analysis of arguments. Meanwhile, the wave of Critical Thinking, understood in this way, has also spread beyond philosophy to all those who want to teach any kind of competence.

Of course, one should learn how to analyze arguments, but one should also know precisely what one is doing. One is offering a specific translation through omission and substitution. On the one hand, it is claimed that the argument is contained within the text, but on the other hand, that the argument remains invisible without translation. Beginners are often led to believe that there should be one correct reconstruction.

Let’s take a closer look. To illustrate this, let’s consider the famous last sentence from Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

– Firstly, you can interpret the sentence positivistically: as a restriction to what can be meaningfully said by the natural sciences. (In this case, you interpret the “must” as descriptive.)

– Secondly, you can interpret the sentence mystically and ethically: as a prioritization of the unspeakable as what is truly important. (In this case, you interpret the “must” as normative.)

– Thirdly, you can interpret the sentence as self-contradictory and, in this sense, therapeutic: because it speaks precisely of something about which one cannot speak. (The “whereof” names something that is indicated as unspeakable in the reflexive pronoun “thereof”.)

These interpretations contradict each other, but can be validated not only by the quoted sentence, but also by the contexts of the Tractatus and later writings. Once you have seen how many conflicting reconstructions of this and other classics exist, you might be quite puzzled by the idea of textual objectivity. It’s clear that the analysis of relevant arguments relies heavily on communication between logically trained readers, where the original text itself is often seen as an obstacle. Instead of focusing on how the negotiation process between readers shapes the reading experience, however, the approach remains one of optimizing the reconstruction of a classic. What emerges could easily be described as fan fiction.**

If we take this seriously and not merely as polemics, it becomes clear that philosophy, in certain schools of thought, is indeed in close proximity to entirely different literary genres. But even the insistence on philologically rigorous reading generally takes the text as the source of the doctrines and modes of thought derived from it, as is also suggested by the general distinction between primary and secondary texts. Overall, this assumption regarding reading can be described as objectivism. But how should we understand this objectivism in our reading culture?

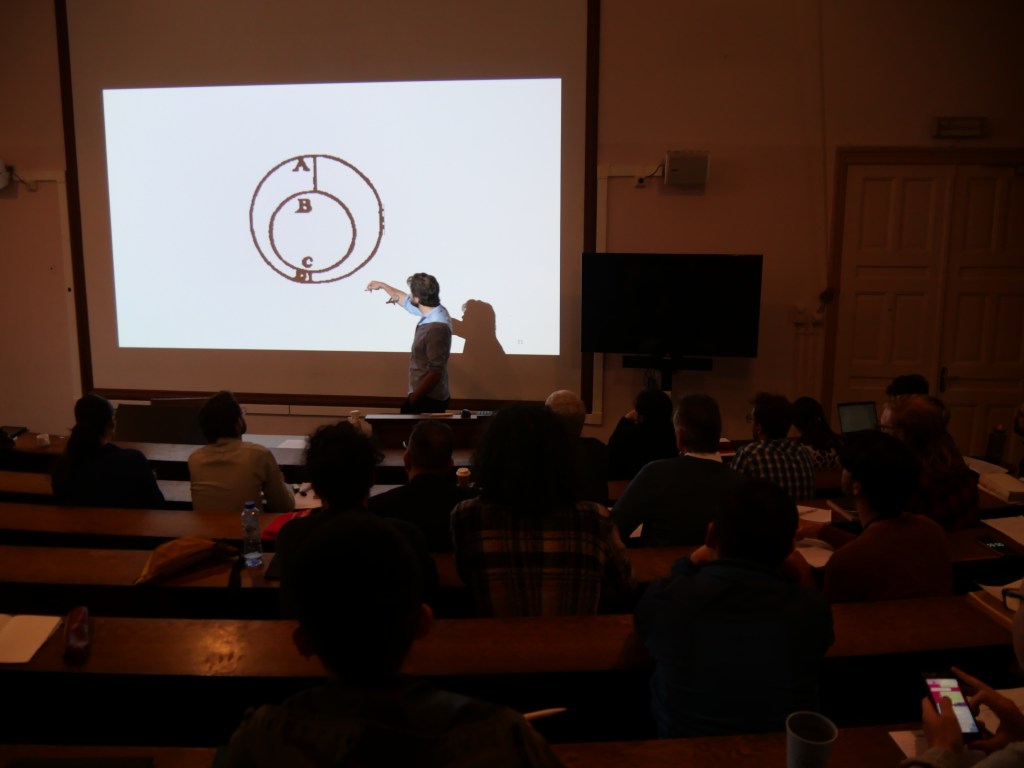

2 The Text as a Possibility of Readings in Interpretive Communities – Objectivism as an Illusion

By objectivism, I mean the assumption that what we believe we have gleaned from the text is actually found within the text itself. On the one hand, this is a correct assumption, because all readers will confirm that they derive their interpretations from the texts. Of course, it must be added here that a text can indeed be read as a chain of propositions that are decodable and whose presence most readers will be able to agree upon. On the other hand, however, it is a misleading assumption, as can be seen from the fact that there are endless disputes about interpretations. Just think of the Wittgenstein quote. If this is true, then objectivism is, on the one hand, correct, but on the other hand, misleading. On the one hand, correct, on the other hand, misleading? Am I contradicting myself here? – Please bear with me. To resolve this apparent contradiction, we must recognize that a text is not identical to its reading. The text is a possibility for reading, while reading is the realization of the possibilities inherent in the text. Following James Gibson, we can speak of affordances that the text offers. As Sarah Bro Trasmundi and Lukas Kosch have shown, a text offers you various possibilities for action or reading. Which possibilities you ultimately choose in your reading depends on further factors. These factors are—so I argue—primarily social. Specifically, this means that whether you read a text in one way or another, and thus what meaning you derive from it, depends on your interactions with other readers.

Of course, you usually don’t even notice this because—especially in our reading culture—you are often alone with a text. But fundamentally, you were never truly alone with a text: As a child, you were, hopefully, read to. As a student, you were constantly corrected by others. And now, now that you’re an adult, you hear voices. Not in a pathological sense. The interactions with other readers are simply mostly implicit, solidified into habits, even traditions. Following Stanley Fish, I would like to call a group that shares certain interpretive habits an interpretive community. Fish locates the negotiation of meaning for texts within corresponding “interpretive communities.” You’ve learned to read menus, and you know what to do with them. And you wouldn’t mistake a menu for a poem, would you? Even before you skim the essay on your table, you know that it contains an argument because it’s a philosophical text—and if it didn’t contain an argument, it wouldn’t be a philosophical text at all. That’s how the tradition of your interpretive community dictates it.

(Taken from this quite insightful podcast.)

It is precisely the fact that a text is not identical with its reading, but rather offers possibilities for reading, that makes us prone to objectivism. The customs of certain interpretive communities are thus presented as properties of the text itself. From this perspective, objectivism with regard to the texts themselves is an illusion.

Now you might say: “Oh, it’s not so bad. Whether I believe I find the customs in the community or in the text itself is irrelevant; the main thing is that I find them!” – That may well be true. However, it becomes a problem when you are looking for something but expect to find it in the wrong place.

3 What Really Generates Objectivity – Reading, just like Singing

So how does reading work? Of course, much can be said about it. But essential points can be understood by considering reading in analogy to singing songs. Let us first return to objectivism.

Written texts have two important properties, it seems, which we also attribute to objective objects: constancy or repeatability and shareability. When I close a book, it seems the text is there constantly, or at least I can read it repeatedly. And when I lend you the book, it seems you can read the same text as me. Thus, these properties of repeatability and shareability seem to be inherent in the text itself.

On closer inspection, however, the matter is different. The aforementioned advantages also arise in a seemingly non-representational activity like singing. Listen to this:

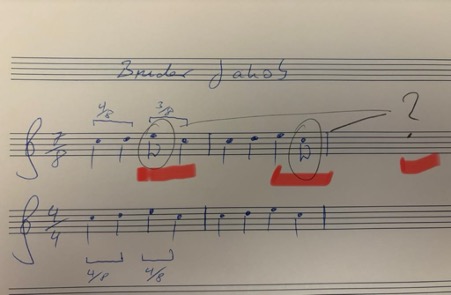

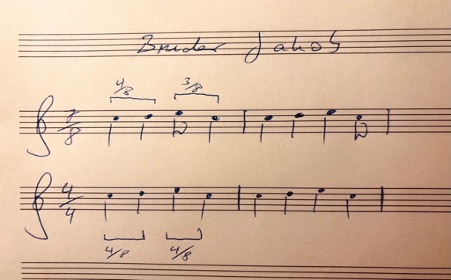

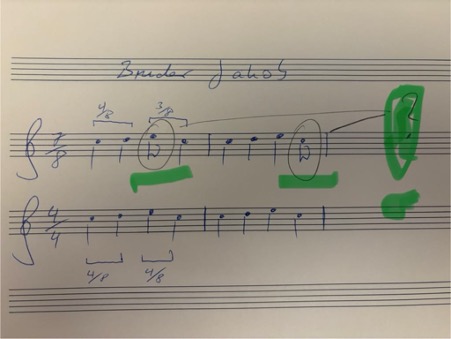

You just heard Bruder Jakob (Brother John, Frère Jacques)! Most of you will not only know it, but could also sing it effortlessly even if you were jolted awake at 3 a.m. Again, the song is consistently in your memory, and you can repeat it. Moreover, others can sing the same song. And you would even recognize it if someone sang it off-key or changed the rhythm.

The song thus possesses a certain objectivity; it is independent of our spontaneous performance and our imagination. But it doesn’t possess this objectivity because it is written down somewhere. If you listen closely, you’ll notice that, firstly, the song is played in a 7/8 time signature instead of the usual 4/4 time signature, and secondly, that it is much more richly harmonized.

The relational object, however, is not a text; there is no physical object to which you could point. Nevertheless, it seems to be an objectively given point of reference. What establishes objectivity despite all the variance is therefore not the physicality of the object, but rather these two properties: repeatability and sharedness with others.*** Sharedness, or rather, repeatability by others, plays the crucial role here. Why? Because without social sharedness, I could not be corrected in my repetitions. Alone, I could mistake any nonsense for a repetition.

Only in agreement with others can there be anything like a correct or genuine repetition. (This is the consequence I draw from Wittgenstein’s private language argument.) Only when you affirm that the 7/8 version is also “Bruder Jakob” is it considered “Bruder Jakob.”

For precisely this reason, in singing as in reading, it is not the physicality, but the shared repetition, that is, the correct repetition, that establishes objectivity. What singing and reading have in common here is that they are embedded in a long history of social interaction.

Like reading, you may have first experienced singing by being sung to, by it being repeated, embodied, shared, and perhaps even ritualized. Just as you were initially read to repeatedly in typical situations: reading and listening were embodied, perhaps in bed with a book and pictures. Shared, that is, perhaps by your mother, your father, perhaps with other children. And perhaps as a bedtime ritual that has shaped your expectations and structured the evening. Singing, like reading, is inscribed within you as a ritual, so to speak. That’s how we learn it. Reading is embedded in these biographical narratives, not just in an abstract tradition.

In my opinion, it is precisely these factors, and especially repeatability and shared experience, that lend objectivity to what is read, objectivity to which the text, much like a song, ‘in itself,’ offers only a possibility.

So what does this analogy with singing offer us? Firstly, it clarifies how, with regard to the factors of objectivity—repeatability and shareability—we ascribe an objectivity to texts themselves, which we actually derive from their social embeddedness; unlike texts, songs don’t have any discernible objects. Secondly, it points us to crucial social sites and situations: if we want to seriously engage with reading, with the negotiation of meaning among readers, then we must go to the places where this actually happens. Accordingly, a philosophical engagement with an 18th-century text would require us to examine epistolary culture, salons, and, more generally, the establishment of conversation as a site of thought.**** While it is quite natural for many of us to have conversations about texts, this form, conversation itself, arose at some point and—this is one of my conclusions from my central thesis—plays a decisive role in the meaning and use of texts pertaining to certain genres. Alongside peer-review processes, conversation is a crucial space where, not least, philosophical reading culture takes place. Accordingly, you can locate the different interpretations of Wittgenstein in very different discussions or communities: the positivist interpretation in the Vienna Circle, the mystical one around Elisabeth Anscombe, the therapeutic one, for example, around Peter Hacker.

The basic idea is thus: The objectivity attributed to texts is an illusion, suggested by properties of reading (actualizing affordances in the text) and projected back onto the text. Reading as a social practice is (like singing) repetitive and socially diverse. It is not the text, but social reading that creates objectivity.

As Suresh Canagarajah puts it: “Meaning has to be co-constructed through collaborative strategies, treating grammars and texts as affordances rather than containers of meaning. Interlocutors draw from other affordances, too, such as the setting, objects, gestures, and multisensory resources from the ecology. Thus, meaning does not reside in the grammars they bring to the encounter, but in the negotiated practice of aligning with each other in the context of diverse affordances for communication. In the global contact zone, interlocutors seek to understand the plurality of norms in a communicative situation and expand their repertoires, without assuming that they can rely solely on the knowledge or skills they bring with them to achieve communicative success.” This is precisely the point I am also trying to make: texts do not contain meanings, but rather offer affordances or possibilities.

4 The Consequences of the Illusion: The Degeneration of Objectivism into Mechanical Reading

If what has been said is true, then it is also possible that certain reading cultures will disappear or change. However, this does not necessarily mean that we will unlearn how to read, but perhaps only that the way we read and the places where meanings are negotiated can change. This is noticeable not only with regard to recent technologies, but also in everyday practice, especially in teaching. I believe, however, that the still widespread illusion that texts themselves are objective is leading to a degeneration in our reading culture. And here I come back to my initial observation that we might be living a scholar’s life with a chapter by Aristotle, while we spend only two hours on a student assignment.

This practice, which, incidentally, is also linked to increasing literacy, the so-called mass university, and the simultaneously stagnating number of lecturers, is initially perceived as stemming from external political pressure—and yet, it is increasingly becoming so entrenched that the guidelines for student text production—for instance, in the Netherlands and Great Britain—are themselves so schematic that one actually believes one can judge after 20 minutes of reading whether the requirements have been met. Such a mechanization of writing and reading is, of course, only justifiable if one believes that texts themselves are objective entities that are accordingly either good or bad. This mechanization is, incidentally, not a consequence of ChatGPT. Rather, it is the other way round: a reading culture that is changing in this direction consistently learns to use such technology.

From the Netherlands, I know that the mechanization of reading is already taking hold in elementary schools, where, from the very beginning, students are taught reading comprehension (begrijpend lezen) in order to test their knowledge of text structure in multiple-choice tests, and then people wonder why most young people have no interest in reading.

It seems that such uninspired role models lead to readers who, in turn, produce texts for exams that are hardly ever read. So why should anyone bother writing them themselves? Why bother reading them?

All of these are developments that, at least at universities, cannot be described independently of the introduction of New Public Management in the 1980s. (What good is it to tell a student to look at the text to understand it if there is hardly any interest in doing so outside of class? No, universities are not ivory towers; rather, cultural deserts have formed around them, in which we see primarily stakeholders instead of interpretive communities. But this criticism is nothing new and also a bit one-sided.)

Because, of course, there are places where the meaning of texts is still negotiated. We find them at literature and even philosophy festivals, on social media under #booktok, in often student-led reading groups, and, of course, in our teaching and research events. Here, reading is sometimes so explicitly social that it is actually performed. This, too, is not entirely new, of course. If we are interested in the foundations of reading, we have to go to these places. What is particularly interesting for our reading culture, I think, is that Large Language Models erode not only trust in the authenticity but also in the objectivity of texts. We are experiencing a massive desacralization of the text. Because unlike the divine authority presumed behind biblical texts, we now constantly suspect a deceptive demon. Accordingly, I believe that the academic rebellion against this desacralization is also a rebellion against the death of the illusion that texts themselves possess inherent quality. To name this desacralization does not mean falling for the grand promises of relevant AI product manufacturers. But we can also use this technology to sensitize ourselves to the fact that it is not the texts themselves, but our reading, our singing, our rituals that create meaning and make it something shared.

5 A Few Conclusions Regarding the Practice of Reading

What are the practical implications of these insights? How can we improve reading practices through such findings? Firstly, I would like to remind you that this research project on reading as a social practice is only just beginning. But if the meaning of texts in reading is essentially unlocked through the interactions between readers, then it helps not to stare at the text itself, but to always ask ourselves first: What do I expect from this text? What am I assuming it’s supposed to tell me? Is it supposed to provide me with an argument for something? What do I do if the text doesn’t meet my expectations? Should I humbly assume that I’m too stupid for it? That I don’t belong to the club of readers who say they understand or even love such texts? And why is this tome even on my desk or in my Adobe Reader?

Once you’ve confused yourself enough with these questions, you can actually look at the text and see what’s written there without immediately searching for “the argument”. People always say you shouldn’t just read, but read thoroughly: But what does “thoroughly” mean? Should I choose lots of colors to highlight the incomprehensible passages? Seriously: This instruction is about as helpful as telling you to concentrate. How do I do that? Stare into space and roll my eyes cleverly? – How do you even know when you’ve concentrated well enough? If you can say something that your conversation partner nods to politely in agreement? I can order from a menu, I can sound good with a poem, but what do I do with a philosophical text? When have I truly understood something? We can still only see this through conversation. – Is that enough, though?

Well, a fundamental insight that follows from these theoretical considerations regarding reading is that a philosophical text offers possibilities or affordances, and thus always different ways of reading it. It is a myth of completeness, particularly prevalent in analytic philosophy, that all implicit possibilities can simply be made explicit. Such completeness contradicts the necessary openness or underdetermination in texts. Think again of Wittgenstein’s famous quote. Another very memorable illustration of this is the duck-rabbit, which, in terms of possibility, remains precisely both. My project would therefore not be to reconstruct the one true argument, but rather to reveal different and potentially conflicting possibilities. Accordingly, one must accept that the text allows for various interpretations, which are only gained within different interpretive communities.

At this point, philosophers usually develop a typical fear of relativism. However, as Stanley Fish already noted, emphasizing possibilities is not about a relativistic position, but about plurality. Such plurality, however, by no means leads to arbitrariness. But what, then, are the limits to this space of possibilities? First, there are of course propositional limits: you cannot say that a text asserts non-p if it explicitly asserts p. Unless, of course, you perceive signs of irony. Here, the matter of limits becomes difficult again; and you will ultimately decide one way or the other. Furthermore, there are situation-specific conditions of appropriateness. If someone asks for directions to the train station, it’s not appropriate to respond, paraphrasing Robert Frost, by musing about less-traveled paths. Just as one shouldn’t sing Frère Jaques at an inaugural lecture or at a funeral. Or should one? Of course, we can break with conventions. For example, it’s entirely up to you whether you sing the song in 4/4 or 7/8 time signature, or even reharmonize it psychedelically with suspended chords. Convention gives you something to play with, or sing with.

Accordingly, Alva Noë makes a crucial point when he compares philosophical texts to scores for thinking, which can also be interpreted in very different ways:

“What the philosopher establishes in their labors are not truths or theses, but rather scores, scores for thinking with. … The philosophy lives for us like a musical score that we – students and colleagues, a community – can either play or refuse to play, or wish that we could figure out how to play, or, alternatively, wish that we could find a way to stop playing.”

I would simply add that, analogous to musical notation, philosophical texts can give rise to a multitude of interpretations. Here we don’t just have a single, obvious interpretation of a duck-rabbit, but a whole zoo with possible shifts in perspective.

Now, that may all sound very nice. But one mustn’t forget that interpretations aren’t chosen arbitrarily, but primarily with regard to social affiliation. If you choose an interpretation, you might belong to a club that’s currently out of fashion. The problem with my musings, then, is that they can be received in very different ways. Academics, in particular, fear reputational damage; therefore, they are very reluctant to admit their lack of understanding. “I don’t understand this text” usually is taken to mean something like, “The author is too stupid to explain it to me properly.” If, on the other hand, one can express genuine and sincere incomprehension, one has truly made progress. But such humility is something one has to be able to afford, so to speak. Therefore, it’s not enough to simply seek conversation; one must overcome one’s shame. You can’t learn to sing well if you’re too afraid of singing off-key.

But at some point, you can truly begin to name the difficult parts and ask yourself exactly where and why you’re stuck. Reflected confusion then becomes a genuine conversation starter. Because if a text offers the possibility of understanding it, it also offers the possibility of not understanding it.

____

* Thanks to Arnd Pollmann for pointing out this passage.

** I borrow this classification from Charlie Huenemann, but I forget in which of his posts it was introduced.

*** See on repetition in music and language Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis’ On Repeat as well as Bente Oost’s vlog on this blog.

**** Thanks to Miriam Aiello for conversations on the topic of conversation.